Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

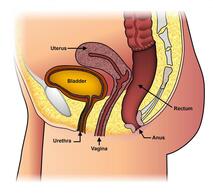

The ability to screen for pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) is a powerful skill for any movement specialist. Although there are anatomical variations depending on the sex of the individual, all patients have a pelvis along with pelvic floor muscles, ligaments, nerves, and fascia that connect the pelvis to the rest of the body. Impairments to the pelvic floor, just like any other area of the body, can appear as tears, strains, weakness, hypertonicity, nerve compression, chronic pain, connective tissue abnormalities, congestion of blood vessels, and more. The pelvic bones are comprised of the innominates (ilium, ischium, and pubis), the sacrum, and the coccyx.1,2 Several soft tissue structures cross the pelvis into the lumbosacral complex and the femoroacetabular joints. Patients may present clinically with movement dysfunction in activities of daily living such as running, walking, and hopping, all of which involve an intricate coordination of the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex.3,4 In analogy, as movement specialists, we are well aware of the relationship between the cervical spine and the shoulder, which consists of the glenohumeral, sternoclavicular, and acromioclavicular joints. Comprehensive care for a cervical spine disorder would involve a shoulder screen and vice versa. Similarly, screening for PFDs during examination and evaluation would provide further value to our patients with lumbar and hip dysfunction due to the close connection among these three areas. The pelvic floor is part of the functional kinetic chain. A problem in and around the pelvic can affect movement up and down the chain. For example, addressing pelvic floor musculature attaching to the coccyx can influence alignment and pain at the sacroiliac joint. Similarly, addressing force closure at the pelvic girdle can influence hip instability. To provide patients with quality care, clinicians who understand basic knowledge of the pelvic floor, including anatomy and function, its influence on the rest of the musculoskeletal chain, and basic screening/management techniques will achieve significantly better and more permanent outcomes. Statistics PFDs typically relate to abnormalities in and around the bowel, bladder, and sexual organs. They include a vast array of diagnoses such as urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence (FI), pelvic organ prolapse (POP), constipation, chronic pelvic pain, coccydynia, dyspareunia, diastasis recti, and many others. Because PFDs involve intimate areas of the body and crucial daily activities such as elimination of the bowel and bladder, they can lead to significant decreases in quality of life.5,6,7 PFDs are present in both the male and female populations, although male PFDs are not researched as well.1 Some PFDs are sex-specific such as erectile dysfunction (ED) in males and postpartum scar tissue adhesions in females. Others are present in both sexes such as urinary incontinence (UI), which is prevalent in 4.4% of men and 35.3% of females.8,9 In the case of UI, like some other common PFDs, prevalence increases with age. While only 5% of men experience symptoms between ages 19-44, 32% of elderly men experience UI.9 Prevalence of ED also increases with age: 2% in men younger than age 40 and 86% in men 80 years or older.10 In a United States 2005-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, about a fourth of all women and nearly 50% of women 80 years or older experienced symptoms of at least one of the following: UI, FI, and POP.11 It is projected that by 2050, there will be significantly more individuals experiencing PFDs than ever.7 As the number of elderly patients increases with every decade, appropriate measures should be taken to educate healthcare professionals and patients on the symptoms, diagnoses, and treatment of these conditions. Barriers While PFDs grow in our society, there is still limited care for patients. This is due to both patient-related barriers and clinician-related barriers. Patient preferences, comfort levels, and knowledge of PFDs can deter them from receiving appropriate care for their symptoms. Sometimes, patients believe that their symptoms are normal, due to outside influences from family and friends as well as advertising products such as pads for UI.12,13 Patients may also find that they want to discuss their symptoms with their healthcare provider, but are too shy and would prefer their provider to initiate the conversation.12 They may lie about their symptoms to avoid examination or may avoid seeing a clinician altogether due to anxiety about the process.12,14 In addition, some women find that costs and inconvenience prevent them from finding care.15 Another patient-related factor that deters care is poor education on pelvic floor anatomy, diagnoses, and treatment. In one study, 61% of peripartum women and 43% of postmenopausal women were not aware of how many orifices exist in normal female anatomy.16 Moreover, due to the large population of Spanish-speaking women in the United States, difficulties in communication and translation may exist between patients and providers. Personal shame and low understanding of medical terms and anatomy are barriers for this population.17 Healthcare providers play a large role in the lack of appropriate diagnosis and treatment for people who present with PFDs. Similar to patients, some providers lack education on prevalence and differences between PFDs and are unable to correctly communicate information to patients.12,18 There is also a general lack of standardization of terms and research, which prevents providers from efficient collaboration.12 Providers themselves are often uncomfortable speaking about PFDs due to lack of knowledge of simple screening tools. As clinicians become comfortable with asking simple questions about bowel, bladder, and sexual issues, they will be better equipped to address these issues in a professional manner and educate using patient-centered language. By creating a safe environment for patients to speak freely, necessary treatment that solves not only local problems but also enhances outcomes of other musculoskeletal pathology can be achieved. Overcoming both patient and provider barriers to discussing and treating the pelvic floor involve learning general anatomy, terminology, function versus dysfunction, and treatment options. If both parties understand what is normal and how to care for PFDs, then much of the hesitation can dissipate and communication would be clear. More importantly, if the healthcare provider is well versed on best practice for PFDs, whether they provide care for it or not, they can serve as the gateway to further educate patients. References 1. Cohen D, Gonzalez J, Goldstein I. The Role of Pelvic Floor Muscles in Male Sexual Dysfunction and Pelvic Pain. Sex Med Rev. 2016; 4:53-62. 2. Raizada V, Mittal RK. Pelvic floor anatomy and applied physiology. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008; 37(3):493–vii. 3. Smith JA, Popovich JM, Kulig K. The Influence of Hip Strength on Lower-Limb, Pelvis, and Trunk Kinematics and Coordination Patterns During Walking and Hopping in Healthy Women. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014; 44(7):525–531. 4. Riley PO, Dicharry J, Franz J, Della Croce U, Wilder RP, Kerrigan DC. A Kinematics and Kinetic Comparison of Overground and Treadmill Running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008; 40(6):1093-1100. 5. McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O'Leary MP, Calhoun EA, Santanna J, Landis RJ, Kusek JW, Litwin MS, Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(10):656–662. 6. Kenton K, Mueller ER. The global burden of female pelvic floor disorders. BJU Int. 2006; 98(s1):1-5. 7. Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(6):1278-83. 8. Maclennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wilson D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. BJOG. 2000; 107(12):1460–1470. 9. Shamliyan TA, Wyman JF, Ping R, Wilt TJ, Kane RL. Male urinary incontinence: prevalence, risk factors, and preventive interventions. Rev Urol. 2009; 11(3):145–165. 10. Prins J, Blanker MH, Bohnen AM, Thomas S, Bosch JLHR. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction: a systematic review of population-based studies. Int J Impot Res. 2002; 14:422–432. 11. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in US Women. JAMA. 2008; 300(11):1311–1316. 12. Wagg AR, Kendall S, Bunn F. Women’s experiences, beliefs and knowledge of urinary symptoms in the postpartum period and the perceptions of health professionals: a grounded theory study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017; 18:448–462. 13. Tinetti A, Weir N, Tangyotkajohn U, Jacques A, Thompson J, Briffa K. Help-seeking behaviour for pelvic floor dysfunction in women over 55: drivers and barriers. Int Urogynecol J. 2018; 29(11):1645-1653. 14. Zoorob D, Higgins M, Swan K, Cummings J, Dominguez S, Carey E. Barriers to Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy Regarding Treatment of High-Tone Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017; 23(6):444-448. 15. Dunivan GC, Komesu YM, Cichowski SB, Lowery C, Anger JT, Rogers RG. Elder American Indian women's knowledge of pelvic floor disorders and barriers to seeking care. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(1):34–38. 16. Neels H, Tjalma WA, Wyndaele JJ, De Wachter S, Wyndaele M, Vermandel A. Knowledge of the pelvic floor in menopausal women and in peripartum women. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016; 28(11):3020–3029. 17. Khan AA, Sevilla C, Wieslander CK, Moran MB, Rashid R, Mittal B, Maliski SL, Rogers RG, Anger JT. Communication barriers among Spanish-speaking women with pelvic floor disorders: lost in translation? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(3):157–164. 18. Mazloomdoost D, Westermann LB, Crisp CC, Oakley SH, Kleeman SD, Pauls RN. Primary care providers' attitudes, knowledge, and practice patterns regarding pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2017; 28(3):447-453. Comments are closed.

|

Dr. GaziWelcome! Learn something of value, solve some of your problems, and feel a whole lot better with Sneha Physical Therapy's blog! Categories |

Sneha Physical Therapy

Copyright 2022 . All Rights Reserved .

Copyright 2022 . All Rights Reserved .

RSS Feed

RSS Feed